“The Cross Laminated Table was designed with the intent to employ a single material to fulfill the fundamental needs of the most basic piece of furniture: a table on four legs. The result is a mixture of engineered wood technology and hand craft, producing a piece of furniture that is not only minimal and elegant but also lively and rustic.”

In 2016, we moved offices and, prompted by the large void that was to be our “meeting room,” decided to initiate an internal project to design and build our own board room table. At the time, we’d also recently connected with a wood researcher at UBC who was willing to assist with fabricating a custom CLT panel from scratch.

The experiment, whether successful or not, would give us insight in the CLT manufacturing process, and also hopefully offer some understanding of the limitations of the material: How thin can we make it? And does it disintegrate when cut down to the dimensions of a typical table leg?

CLT, or Cross Laminated Timber, is an engineered composite wood product comprised of layers of smaller wood pieces arranged in alternating layers oriented 90 degrees to one another, giving the finished panel structural capacity in two directions. CLT is commonly formed from layers approximately 1.5″ thick resulting in panels at least 4.5″ thick for a three-layer panel. (It is also commonly made with 5 or 7 plies, for a 7.5″ or 10.5″ panel: Great for buildings, but not so great for tables.)

CLT has gained much popularity in recent years as a replacement for other structural mass materials such as concrete, due to its relatively benign environmental impact (using wood as a natural, renewable resource) and it’s erection speed on site, where panels are pre-fabricated off-site following a design/shop drawing process and merely lifted into place like one might do with steel.

Table design options: primarily testing various leg options to find a correctly proportioned but strong configuration

During early explorations we knew the panel needed to be thinner, not just because 4.5″ of solid wood is extremely heavy, but aesthetically the table wanted to be as thin as possible — ideally 1.5″ or less.

CLT is visually interesting on its own — the panel faces appear like parallel butt-jointed boards and its edges display alternating layers of parallel grain and end grain — and one could simply attach a set of pre-manufactured table legs and create a fine product. However, we felt a table constructed from this singular material (legs included) was a more conceptually rigorous approach, and would achieve the monolithic expression we desired.

Table leg research: all dissatisfying

After iterating through various design options, we settled on a 3’x6′ table top with tapered wood legs cut from the same 1.5″-thick CLT panel. The edges of the table and legs employ a simple but effective beveled cut that makes edges appear paper thin from some angles, and also exaggerates the unique alternating grain pattern of the CLT along the table edges and the legs.

The process began with a pile of “green” 2×10 Douglas Fir boards that had been left exposed to the Vancouver weather for an undetermined amount of time (perhaps 1-2 years), essentially waste lumber. The boards were split and planed to achieve consistent 1/2″ thick pieces, then aligned and glued edge-to-edge to create each lamination layer. The layers are then “crossed” and glued before being squished in a hydraulic press.

2×10 boards cut and planed to size

preparing the laminations

the panel in the press

beveling the table top edges

Despite thinning the panel, the resulting slab was still quite heavy, causing some concern that the rather delicate legs may not be able to support the table and would require redesign or reinforcement. Introducing steel was an obvious solution, but undesirable as we wanted to maintain the singular material approach. The other challenge involved geometrically resolving the 3-way miter join at the corners where each leg meets the table top.

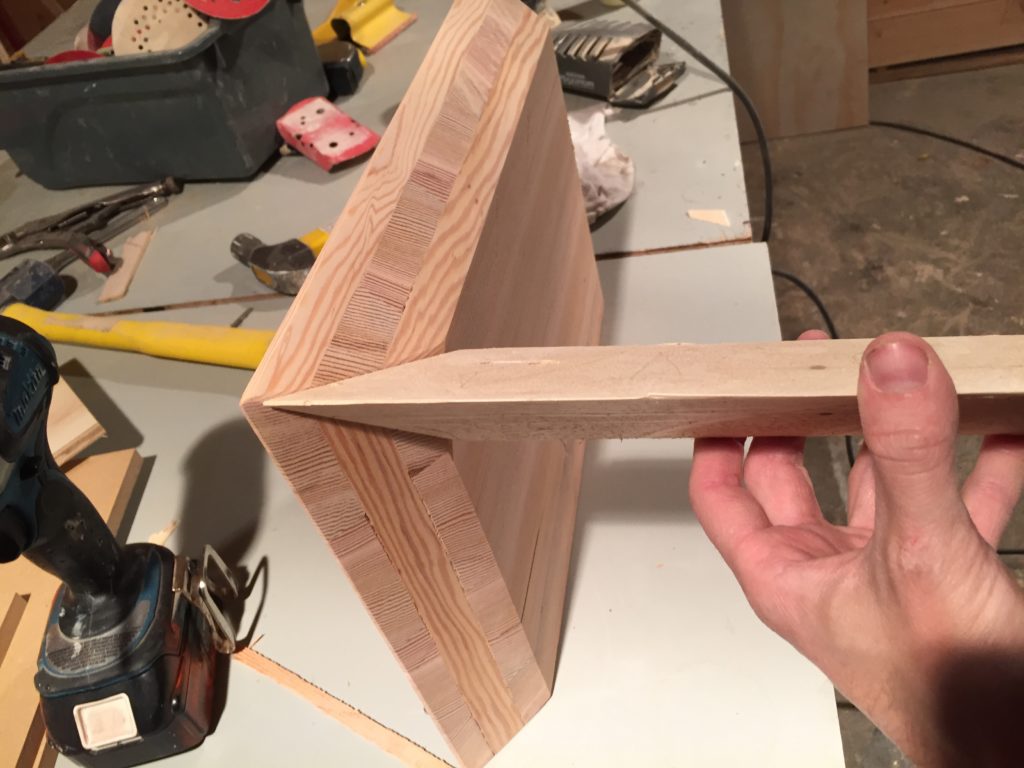

an early proof of concept test fit: resolving this detail required careful planning and construction

After some in situ test fits, we opted to increase the cross-sectional area of the leg at the connection, improving the joint’s moment resistance (to prevent racking) and allowing for a stronger biscuit joint. The joint profile itself is moderately complex but this complexity is concealed and the finished surfaces blend together nicely once sanded and filled.

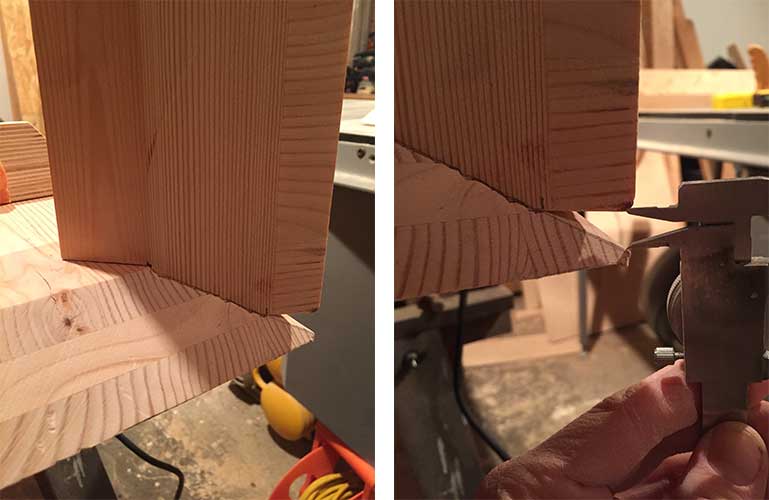

test fits on the actual panel

confirming the biscuit connection depth

preparing each side the table-leg connection

The Cross Laminated Table will be featured in the Prototype exhibition at IDS Vancouver this fall: “a juried platform featuring products not currently in production addressing new ideas for the residential market.” Following the exhibition, we intend to fabricate a second version to see if the panel can be thinner or the joints strengthened further, with the eventual goal of making the table available for purchase in a “built to order” fashion that would permit custom sizes, wood species, and finishes.